The Complex Life of a Captive Orca: Why the Debate Over Marine Parks Continues

The tragic death of an orca trainer is more than just a shocking news story; it is a stark reminder of the fundamental conflict between the natural world and human entertainment. While these rare and horrifying incidents rightly draw global attention, they are often a symptom of a much larger issue: the scientific and ethical debate surrounding the welfare of orcas in captivity.

This article moves beyond the specifics of any single tragedy to explore the core reasons why these majestic predators, so powerful in the wild, have become the focus of a heated and ongoing controversy.

A Life Unsuited for Confinement

Orcas, often called “killer whales,” are apex predators that thrive in the vastness of the world’s oceans. Their biology and social structures are a testament to a life in the wild that is fundamentally incompatible with the confines of a concrete pool.

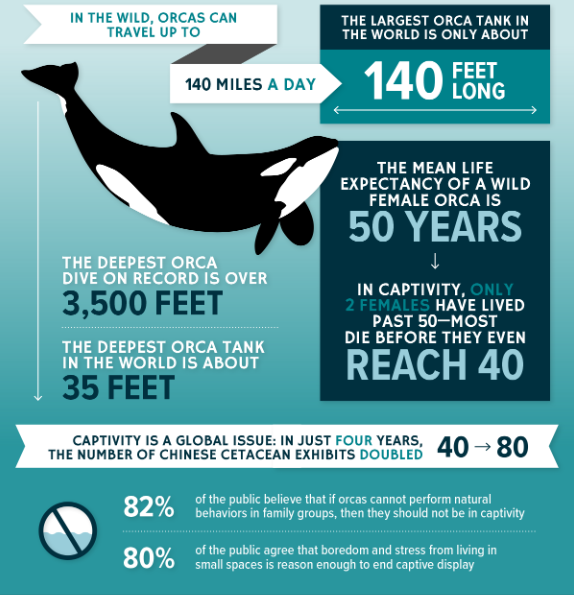

- Vast Habitats: In the wild, orcas can swim up to 100 miles (160 km) per day. A typical marine park tank, by comparison, is effectively a small bathtub, a mere fraction of their natural territory. This extreme confinement can lead to stress, boredom, and repetitive behaviors.

- Complex Social Pods: Orcas live in highly intricate social groups called pods, which are essential to their mental and emotional well-being. Captivity often disrupts these pods, mixing orcas from different geographical regions who speak different “dialects,” leading to social conflict and aggression.

- Physical Ailments: The physical consequences of captivity are visible in conditions like collapsed dorsal fins, which affect nearly 100% of captive male orcas. While this doesn’t appear to be painful, it is a clear indicator of an unnatural life, as it is a rare occurrence in the wild.

The stress from these conditions can manifest in unpredictable and dangerous ways, posing a risk not only to the animals themselves but also to the humans who interact with them.

The Trainer’s Bond and the Inherent Risk

Trainers and caregivers at marine parks often form deep, personal bonds with the animals they work with. They are highly skilled professionals who dedicate their lives to the welfare of these creatures. However, even the most profound bond cannot eliminate the inherent risks of working with a powerful, wild animal.

Tragic events, such as the death of Dawn Brancheau at SeaWorld in 2010, have served as a grim testament to this reality. The incident, which was investigated by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), led to the conclusion that no amount of training could guarantee safety when working in close proximity with such powerful animals. It forced the public to confront the difficult truth that the animal’s natural instincts can never be fully suppressed.

A Shift in Public Consciousness and the Path Forward

The tragic incidents involving orcas and trainers, amplified by documentaries like Blackfish, spurred a profound shift in public opinion. The once-unquestioned practice of keeping orcas for entertainment began to face widespread criticism. As a result, marine parks have been forced to change their policies, signaling a new era of animal welfare.

Today, there is a strong push for a future that prioritizes conservation and education over performance. Organizations are developing sea sanctuaries, large netted-off areas in natural ocean environments, to provide a more humane alternative for the remaining captive orcas. Additionally, major parks have ended their orca breeding programs, signaling that the current generation will be the last to live their lives in captivity.

The conversation sparked by a series of devastating events continues to shape the future of marine wildlife conservation. It reminds us that our understanding of these incredible animals is still evolving, and that our relationship with them must be guided by respect, ethics, and a commitment to their natural well-being.